She says, "It's a strange thing because it's exactly what I thought I would be worried about but I haven't been because I thought, 'Well I've done what I needed to do. I've done everything I needed to do.'"

She says it's a relief to be free of the pressure to, for example, avoid air conditioning, cold winds, any sort of chill on her back, to avoid shaking hands or physical contact, to constantly be careful about what she eats, to be constantly on high alert for anything that could affect her voice. "Everything was a pressure," she says.

She told the BBC in 2017, "I don't want to hear it anymore because it was good. It was beautiful. I had a beautiful voice, but now at 75 years of age, if I listen to it again it's not like it was at 35, 40. It's nothing like it."

She no longer even wants to talk about the life she led when she had that voice. I know that because she tells me, more than once, during our interview: "Be nice!" she says. "Don't go to the old-fashioned, 45-50 years ago."

She says, "Be nice" on at least four separate occasions, sometimes in a mock-threatening manner, her voice dropping a precisely modulated amount to a tone of pure, distilled, intimidatory authority.

"Be nice!" she says. "They'll come and get you. They know where your family are."

Journalists have often alluded, in articles like this one, to her fierce reputation. About this, she says: "They're fearful of me. I get a lot of that."

"Why is that?" I ask.

"I've seen so much negative stuff. So I just put them at ease by telling them, 'Be nice!'"

I ask about the time John Copley, the producer of her breakout performance in 1971's The Marriage of Figaro, said he initially thought of her as, "A great trial, very boring girl, very lazy."

"Yeah," she replies, "but you're going back 45 years. You have to modernise things."

She goes on: "Don't go too much into the backlog of all the stuff. It's rather nice if you do something rather fresh because I'm 75 now and things have happened in the last two or three years that have been quite amazing."

The amazing things are the emergence and appearance on important stages around the world of the young New Zealand singers she has mentored and supported through her eponymous foundation, which she started in 2004. The foundation is the main reason she's doing this interview, or any interviews, because with the publicity comes the prospect of donations. It's a trade-off she has to make because opera is not the force it was when she was its global face in the 70s and 80s, and money isn't exactly flushing itself into its coffers.

Anyway, that's enough of the present. Let's now go into the backlog of all the stuff.

Imagine how often she's been forced to pore over her storied life. There have been three This is Your Lifes (2xNZ, 1xUK), thousands of media interviews like this one, endless public appearances, speeches, Christmas barbecues with friends and acquaintances. In 1990, Britain's favourite intellectual arts-based broadcaster Melvyn Bragg spent a year following her around the world in order to make a feature-length documentary about her life.

How dull and empty to be made once again to look back over this over-examined life, to once again be forced to talk about making it to Covent Garden (the All Blacks of the opera world) in her late 20s (the late teens of the opera world) and of performing at 1981's royal wedding (the royal wedding of the opera world).

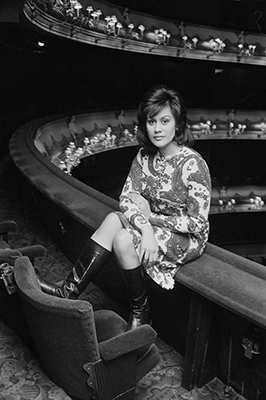

Nevertheless: Her breakthrough was in 1971, at the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden, one of the world's great opera houses, when she sang one of the most famous and challenging roles in opera, the role of Countess Almaviva in The Marriage of Figaro, at which point she became, overnight, one of opera's biggest stars.

The review by Financial Times critic Andrew Porter was indicative: "Such a Countess Almaviva as I have never heard before."

In an interview with the Academy of Achievement, she described the aftermath: "Suddenly, you've got agents and jobs, and you're doing this and doing that. You're wanted everywhere. And there's interviews and newspapers. And the Met's calling and Covent Garden is booking you again."

She is a product of her time, which began in 1944, when she was born to parents she never speaks about, and was soon after offered for adoption to a family who initially rejected her because the man who would become her father - Tom Te Kanawa - wanted a son. The woman who would become her mother, Nell, accepted her on the second offering a few weeks later when Tom was out.

She trained remorselessly during and after her school years, under legendary Auckland-based teacher Sister Mary Leo. As a teenager, she sang Ave Maria late at night in grimy Auckland nightclubs, apparently bringing hardened old boozers to tears, then she won big-time, prestigious singing competitions like the Mobil Song Quest and Sun Aria here and in Australia, and in 1965 she left for the United Kingdom already very famous in New Zealand, with a level of success described by the also-famous Max Cryer as "extraordinary and unprecedented".

Two years later, she returned for her wedding in Parnell where she was mobbed by the public outside the church. Woman's Weekly called it the wedding of the year.

Back in England, her international star began to rise. When she first auditioned for the role of the Countess at Covent Garden, the conductor, Colin Davis couldn't believe his ears: "I remember the first time I saw you," he told her later on This is Your Life, "We hadn't met, actually, and I thought that was the most beautiful voice I'd ever heard in my life." Sir Georg Solti, the musical director at Covent Garden said in a later television documentary, "I hear hundreds of people in a year: piano players, violinists - really hundreds - and maybe once or twice a year I sit up. And that was Kiri's audition."

This is the sort of effusive, high-level outpouring of adulation that would come to mark her career and help make her one of this country's most internationally famous people.

From 1971 on, it was basically gravy. She travelled the world, singing at the great opera houses of Europe and beyond. She sang Let the Bright Seraphim at Westminster Abbey during Charles and Diana's "Wedding of the Century" (600 million viewers. Prince Charles: "My favourite soprano", "Glorious voice", "One of her greatest fans"), she was made a Dame the next year, took the role of Maria in Leonard Bernstein's 1984 recording of his hit musical West Side Story, sang Now is the Hour at the Commonwealth Games Closing Ceremony in 1990, sang the Rugby World Cup anthem World in Union on the UK's Top of the Pops in 1991, and was chosen to lead the singing of Rule Britannia at the Last Night of the Proms in 1992.